Report: Oberhausen International Short Film Festival 2023

I was privileged to have been invited to Oberhausen International Short Film Festival (Germany, 26 April to 1 May) by Dr Lars Henrik Gass, Festival Director, Katharina Schroder, Theme Coordinator and the programme curators, Dmitry Frolov and Vladimir Nadein for the first programme of avant-garde and experimental machinima films at a major European film festival to take place. I was also delighted to see machinima work, created by Alice Bucknell, featured on the programme magazine’s front cover too! I was there, primarily, to participate in a panel discussion with Gemma Fantacci, one of the organisers of the Milan Machinima Film Festival, and two artist-curators from the US and Hong Kong respectively, Alice Bucknell and Ip Yuk-Yiu.

Programme

The programme, entitled Against Gravity, was themed to loosely represent a video-game/machinima creative experience, from Starting the Game, Holding the Controller, Crack the Code, Don’t Forget to Save, Opening the Map, Unlock the Real, Cosplay As…, and a retrospective of Phil Solomon’s work, called Interplay, a filmmaker whose turn to machinima in later life was the inspiration for the festival theme. As one might expect, the organizers dive into each sub-theme to tease out their narrative through a selection of works across a span of 27 years of machinima practice. Unfortunately, I didn’t arrive in time to see all the selections, but the ones I did see were very interesting.

Image: Programme Cover (link to Festival programme here)

Many of the films were ones I had not previously seen – experimental films tend to be distributed in a different way to traditional machinima, using mostly artistic channels, and so often make their way directly to independent film theatres and galleries as a consequence. This of course diverges from the traditional approach to machinima-making of community-shared content, through which debate and practices are openly discussed. What was interesting with the presentation was the mix of older work with more recent pieces, effectively positioning machinima in a narrative of avant-garde practice and demonstrating experimental applications by artists/filmmakers for an audience that clearly had interest in the work if little experience of machinima or games specifically. I got the distinct sense of the emergence of a new generation of machinima fans – both creators and audience – and also the sense there is demand for a new way to experience machinima on larger screens from this audience, especially with technological advancements that make quality of content higher resolution and approaches employed by artists accessible in the experimental tradition of film viewership.

It was also interesting that the foundation of machinima was considered relevant to the presentation of avant-garde works both because its origins lie within 3D real-time games engines and also because the use of game as a creative matrix for storytelling beyond gameplay conveys subversion, virtuality and transcendence – all themes that resonate well with the experimental arts movement. Drawing on Solomon, however, the rationale for including machinima was the transformation from analogue forms of film to digital, with all the nuances that brings – relating to the breadth of creative practices, methods of transferring work for exhibition, storage and also presentation to audiences. What was interesting in this is that many at the festival seem to have little conception of either the term machinima, the game communities from which it emanates or its impacts on popular online culture. Filmmakers selected appear to have forged their own practices, sometimes as multimedia artists, using games as found tools and environments. Some were clearly also a little reticent about being associated with its background and origins, the taint of the M.com years, and probably alongside that the many issues the community has collectively faced in relation to the recognition of originality, ownership and authorship of works created.

Of the themed selections I saw, in Open the Map, the idea that games whet the appetite for utopian experiences was demonstrated through the selection of two films. The first was a documentary about a group of queer teenagers living through the challenges of Covid by escaping into Minecraft to connect with each other in a virtual safe space they made their own. The film, Tracing Utopia (2021), was directed by Nick Tyson and Catarina de Sousa, and was based on their observations of working with the teenagers over an extended period of time. It highlighted well the essence of community and collaboration, something that has always been the heart of machinima. The second was Alice Bucknell’s three-channel installation converted for the festival to a single channel, called The Martian Word for World is Mother (2022). This film was made in Unreal Engine and showed three different visualisations of Mars (the Green, the Blue and the Red), each being a post-human perspective on the future colonisation of the planet, drawing inspiration from popular sci-fi tropes on the interplay between ecological, economic and political ideologies. These include Elon Musk (terraforming), Donna Harraway (Cyborg Manifesto), Ursula K Le Guin and Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2009 Mars trilogy, among others. It is Bucknell’s Blue Mars that is shown on the front cover on the Oberhausen Film Festival programme, illustrating how multinational organizations convert permafrost into water for sale back to Earth – something she presents as a speculative near future. Not exactly a vision of utopia per se but her Green Mars was an interesting approach to reflecting on how the technologies used to exploit Mars in her Red and Blue versions may help Mars bring back to life its former natural habitat for its own end. She includes a mystical (textual and aural) language that was created using Scottish Gaelic, Helene Smith’s invented Martian language and sounds of Arctic wind, created using a text-to-speech AI and the assistance of OpenAI’s GPT-3. A fascinating creative process and captivating to watch and listen to.

image: Tracing Utopia

In Unlock the Real, older films were used to position machinima through documentaries, for example Harun Farocki’s Parallel I (2014) showed how games have advanced in their representation of assets such as trees, clouds, water and fire from the earliest machine dashes in the 1980s, to squares of the early 1990s, to more modern mesh representations such as in GTA in the 2000s. That reflective process of course, with recent developments in the representation of fluid, skin and movement dynamics integrated now into so many tools that creators use, whilst incomplete in Farocki’s work perfectly illustrated how games have focussed on advancing realism. This was then followed by works that demonstrated aspects of even greater realism, from shape and form, to speed of movement (Benoit Paillé’s Hyper Timelapse GTAV, see below), to representation of human experiences and the interplay between virtual and real, and even the way that in-game corruptions of brands really don’t hide what they represent any more (Jacky Connolly’s Decent into Hell, 2021). Indeed, Connolly’s clever interweaving of photographs and real film into the GTAV landscape was quite a trippy experience. It is not often one sees that trajectory so clearly but Vladimir and Dmitry’s curation made it easy for less experienced machinima followers to make the connections between virtual game worlds, film and real-life experiences.

Benoit Paillé’s HYPER TIMELAPSE GTAV (CROSSROAD OF REALITIES) (available on Les Nuits Photo Festival Vimeo channel, released 30 Nov 2015) –

The Phil Solomon retrospective, themed Interplay, was equally fascinating, with introductory comments by Ip Yuk-Yiu and Lynne Sachs who both knew him personally. Solomon was a key influencer in the US avant-garde film scene, and one of his early works had previously won an award at the Oberhausen Film Festival (Remains to be Seen, 1990 – a clip of which you can see on this Vimeo channel). Vladimir and Dmitry selected two of his early photochemical 16mm films: The Secret Garden (1988) and Twilight Psalm II: ‘Walking Distance’ (1999). These had a mesmerising depth to them apparently achieved by applying an emulsion to each frame and then transferring it using an optical reader. They were juxtaposed with the subsequent selection of Solomon’s tribute following the passing of his lifelong friend, Mark LaPore, in a trilogy of machinima films made using GTA (San Andreas). The trilogy was called In Memoriam: Rehearsals for Retirement (2007), Last Days in a Lonely Place (2007) and Still Raining, Still Dreaming (2008). Interestingly, Yuk-Yiu commented that he never fully appreciated Solomon’s machinima work when it was released. This was primarily because he could not see a connection to his previous work yet the interplay was evidently between chemistry and code (analogue and digital) techniques as well as presence/absence represented by the virtual world. However, the rather melancholic scenes in the machinimas, which seemed to somehow represent Solomon’s search for his friend through the glitches in the game world, may also have been connected through another film that Solomon made with LaPore in GTA, released just a few days before he died, called Crossroad (2005).

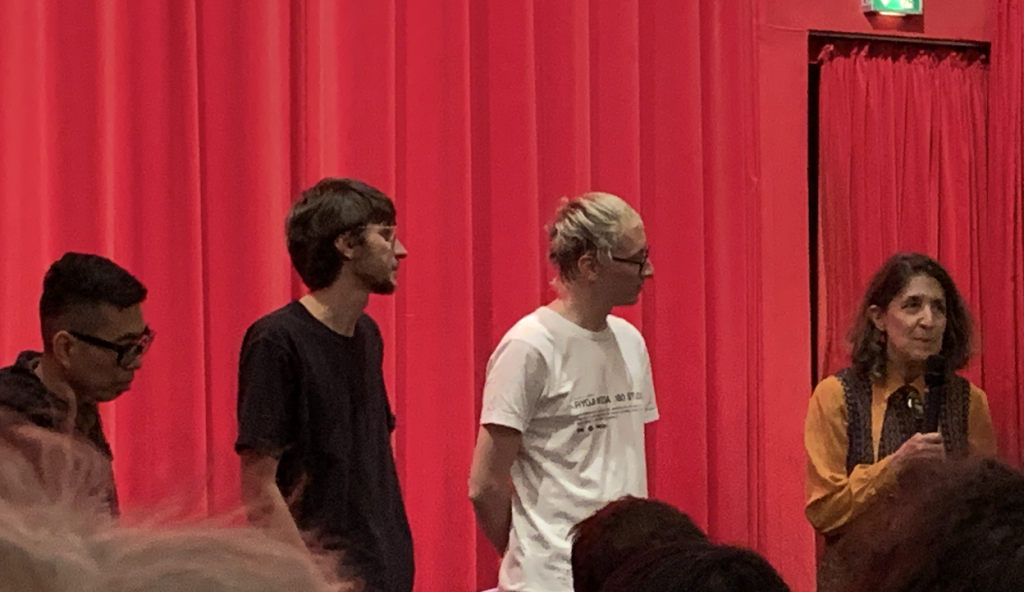

image: Vladimir Nadein and Dmitry Frolov introduce Interplay with Lynne Sachs (right) and Ip Yuk-Yiu (left)

Panel Discussion

I really enjoyed the opportunity to participate in the panel discussion as well as the various follow-up chats with others visiting the event. On the panel, each of us had very different experiences and perspectives of machinima, and we were asked some great questions about how we came to machinima, how we see it evolving and what its future will be. A question that emerged was at what point is the term machinima no longer relevant. From an avant-garde perspective, some questioned whether machinima’s history got in the way of framing their work. Well, of course, many of us long-timers have had those discussions over the years but it was interesting to hear others discuss this too. I really liked how the critical reflection suggested that it is its adaptability in reflecting latest technological and game advancements as ‘machine cinema’ that keep it apart from other creative practices – an observation I like to think the pioneering Hugh Hancock would have been supportive of.

Machinima is also clearly a good fit with the avant-garde scene, which of course is well reflected in Matteo Bittanti et al’s VRAL Patreon project, where you can find monthly film selections and interviews with creators. Matteo is also one of the founders of the Milan Machinima Film Festival, along with Gemma Fantacci, a student of game-related counter-culture, whom I had the pleasure of meeting in person for the first time in Oberhausen (although earlier this year we also chatted for the Digra Italia talks series). Indeed, a number of the directors included in the machinima theme at Oberhausen were ones the Milan team have featured, as indeed have we on the CM podcast.

Another interesting audience question was also about the nature of 3D and its continual re-emergence in film, and how it differs in games. It was clear that with a primarily film-based audience, some struggled to appreciate the nature of 3D and realtime concepts that are so well understood in game worlds. Of course, anything rendered for a 2D screen immediately makes it difficult to imagine depth dimensions, or indeed the methods used to capture and edit scenes, for example using mod tools within 3D environments. Part of the reason is the different uses of the term 3D: in-game experiences are a 2D illusion of a 3D representation rendered through a screen. 3D films in contrast are a fixed view perspective generated by overlaying stereoscopic views. I’m sure they exist but, thinking about this, I don’t recall ever having seen a 3D stereoscopic machinima. Nonetheless, the nature of machinima remains a challenging aspect to communicate and convey – as indeed do the differences in the experience one has when viewing the work in a publicly shared environment such as a cinema, gallery or arcade compared to desk-based screens, handheld or even hyper-personal VR screens. For example, most machinimas we review on the CM podcast have never been intended for consumption on the ‘big’ screen and it certainly isn’t made using large format screens. This is something I recall thinking about at great length for the 2007 European Machinima Festival as well as the various showcases of works I’ve made over the intervening years, not least because detail is emphasized in ways that is never really experienced in a 3D game environment. And even though many avant-garde works are intended for larger format screens, this aspect does not seem to be a particular focus of directors. Thus, the 3D/2D transformation highlights another important yet completely unexplored and unappreciated aspect of machinima as avant-garde or experimental film, perhaps related to the closed distribution methods and consumption experience design strategies used as previously highlighted.

In sum, Oberhausen International Short Film Festival was a fascinating in-depth review of different avant-garde perspectives on machinima. It was a real pleasure to have time to talk to some of the participants in the programme who made the journey from across the world to attend. I was especially thrilled to see the baton for the development of a new appreciative community being picked up by Dmitry and Vladimir – the huge effort they had made in devising the programme, engaging with creators and connecting the dots across the generations of machinima and filmmaking traditions was outstanding, and evidenced in most of the theme sessions selling out. I was really pleased to hear they are potentially going to be doing more of this in future and I’m certainly looking forward to catching up with them soon to hear their reflections and future plans too.

And finally, something I haven’t experienced since I was a teenager was the beautiful plush setting of the cinema in which the programme took place, complete with red velvet curtains and projectors (when required) at the Lichtburg (meaning ‘fortress of light’) Filmpalast Gloria auditorium (see above). Oberhausen is the oldest German short film festival, founded in 1954, and one of the most significant for the development of production conditions in Germany. In 1962, the Oberhausen Manifesto declaration by 26 filmmakers at the eighth festival is attributed with having created the basis for the success of New German Cinema worldwide. I therefore thoroughly recommend finding the time to visit and support a future festival.

Summary of Themes and Films

A listing of the films shown for each theme is as follows –

Start the Game

Everyday Daylight by Total Refusal (Austria), performed live with GTAV

Hold the Controller

Dance Voldo Dance by Chris Brandt (2002, Soul Caliber)

My Own Landscapes by Antoine Chapon (2020)

How to Fly by David Blandy (2020, GTA)

But I wanna keep my head above water by Federica Di Pietrantonio (2022, Sims)

Crack the Code

Ain’t Free by George Roxby-Smith (Second Life)

It’s in the Game ’17 by Sondra Perry (2017)

Why Don’t the Cops Fight Each Other by Grayson Earle (GTA)

Don’t Forget to Save

Codes of Honor by Jon Rafman (2011, Street Fighter IV)

The Grannies by Marie Foulston (2021, Red Dead Redemption 2)

Le Moment Fabriqué by Alan Butler (2017, GTA)

End Time and the Trajectories of Ancestors by Edwin Yun-Ting Lo (2022, Far Cry 5)

Open the Map

Tracing Utopia by Nick Tyson and Catarina de Sousa (2021, Minecraft)

The Martian Word for World is Mother by Alice Bucknell (2022, UE4)

Unlock the Real

Parallel I by Harun Farocki (various)

Hyper timelapse GTA V (crossroads of realities) by Benoit Paillé (2014, GTA5)

Decent into Hell by Jacky Connolly (2021, GTA5)

Cosplay as …

Rotterdam Tower by Clint Enns (2010, GTA4)

Sidings of the Afternoon by Gina Hara (2021, Minecraft)

Interplay (Phil Solomon)

The Secret Garden (1988)

Twilight Psalm II: ‘Walking Distance'(1999)

Rehearsals for Retirement (2007) (GTA)

Last Days in a Lonely Place (2007) (GTA)

Still Raining, Still Dreaming (2008) (GTA)

About the Machinima Curators

Vladimir Nadein (b. 1993, Moscow) is a curator, artist and film producer based in Taipei, Taiwan. His works were presented at the solo exhibition Deep Play, VT Artsalon and Greater Taipei Biennale. He produced an award-winning film Detours, supported by Hubert Bals Fund, received the Eurimages Lab Project Award at Les Arcs Film Festival and was shown at Venice Critics’ Week, Viennale, Thessaloniki IFF, Berlin Critics’ Week, FICUNAM, Jeonju IFF, IndieLisboa, Beldocs, FILMADRID, Camden IFF, TFAI, Barbican Centre among others. In 2016, Nadein co-founded the Moscow International Experimental Film Festival and directed it for five editions. He curated special programmes and screenings for the 17th Venice Architecture Biennale, Hamburg Short Film Festival, Moscow International Biennale for Young Art, Garage Museum, University of California, Los Angeles and other venues. Nadein tutored at the Moscow School of New Cinema and is a member of the filmmaking duo together with Dina Karaman.

Dmitry Frolov (b. 1988, Kaliningrad) is an art and film curator and researcher based in Izmir, Turkey. He holds a BA in Сultural Studies from the Russian State University for the Humanities and an MA in Film Programming and Curating from Birkbeck, University of London. He has curated a variety of screenings, panels, performances and exhibitions dedicated to such artists as Maya Deren, Chris Marker, Tony Conrad, Vladimir Kobrin, Yoko Ono, Michael Snow, Annabel Nicholson, James Benning, Alain Cavalier, Aura Satz, Cao Fei, Ana Vaz, Cyprien Gaillard, etc. His texts have been published in Iskusstvo Kino, Spectate, Colta.ru, Syg.ma and other media. Since 2017, he has been working as a curator at the Moscow International Experimental Film Festival (MIEFF). Currently, he is also working as a film curator at Pushkin House, London.

Addendum – How’s Your German?!

Some great write-ups in regional press here –

Der perfekte Wind oder die Kunst des Fallens by Philipp Stadelmaier, 27 Apr, Filmdienst.de

„Machinima“-Filme – die nächste große Kino-Revolution? by Magnus Klaue, 2 May, Welt.de

Wie Sisyphos im Videospiel by Michael Ranze, 2 May, Faz.net

Die Alten und die Jungen: Von Selbsthistorisierung und Computerspielindustrie: Am 1. Mai endeten die 69. Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen by Manfred Hermes, 3 May, Jungewelt.de

Kurzfilmtage Oberhausen – Signaturen unserer Zeit by Lucas Barwenczik, 8 May, Film Dienst

Zeit zum Totschlagen: Oberhausen und Games im Kino by Frédéric Jaeger, 8 May, Critic.de

Machinima: A cinematic world through video games by Aleksander Huser, 5 June, Modern Times Review

Recent Comments